By Henry Stimpson, Contributing Writer

FRAMINGHAM – Let’s journey back to Framingham in 1750. You’d travel on dirt roads across fields and forests in a rustic town of about a thousand souls. Much of it was “very open farmland,” said Ruthann Tomassini, research volunteer at the Framingham History Center.

On his property along Cochituate Brook, William Brown raised cattle and ran a gristmill and a fulling mill powered by the rushing water. (A fulling mill pounded raw fabrics with mallets.) There you’d find a young giant, of mixed African and American Indian ancestry, working the mill cleaning cotton imported from the South.

At 27, Crispus Attucks had probably spent his entire life enslaved. A bit knock-kneed, he stood at six feet and two inches, towering over the average man of the day. A smooth talker considered honest and loyal, Brown trusted him to buy and sell cattle and allowed him to travel independently.

No one could have predicted that 20 years later, his death as the first victim of the Boston Massacre would make him an icon of the patriot cause.

Framingham roots memorialized on bridge

Photo/Henry Stimpson

Attucks was born just over 300 years ago in 1723 on Hartford Street near the Natick line, Tomassini said. His father was an enslaved African and his mother a Wampanoag Indian who may have been descended from John Attucks, hanged for treason during King Philip’s War. An 1887 history of Framingham claims Attucks’ family lived in an “old cellar-hole.” The cellar, as well as Brown’s house and mills, are long gone, but the large white house erected in 1807 by his grandson still stands on Old Connecticut Path.

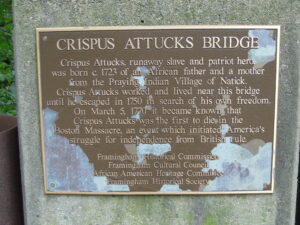

Nearby, the Crispus Attucks Bridge crosses the brook. On the southbound side is a flaking bronze plaque. “Crispus Attucks worked and lived near this bridge until he escaped in 1750,” it reads in part.

Attucks was an accidental hero, Tomassini points out. Some residents wanted the bridge to instead honor Peter Salem, a former enslaved man in Framingham who fought with valor in the Battle of Bunker Hill. After much debate in the town, the plaque was installed in 2000.

From slavery to freedom on the seas

Despite—or maybe because of—the latitude given to him by Brown, his owner, Attucks couldn’t resist the lure of freedom. In September, he ran away and probably escaped to Nantucket where he signed on as a harpooner on a whale ship. Sailor was one of the few jobs open to a non-white man. When he wasn’t at sea, he was a ropemaker.

But Tomassini believes Brown freed him. “It’s difficult to think he ran away,” she said. Tomassini, 83, retired at age 67 from a career in the food industry and began volunteering for the Framingham History Center a year later. “Research intrigued me,” she explained. “Every day there’s something new.”

Brown, however, did place an advertisement in the Boston Gazette offering a reward of ten pounds for the return of his slave, “Crispas.” (Enslavers often bestowed Roman names like Crispus, meaning “curly-haired,” to show off their classical education.) For 20 years he was just another anonymous mariner using an alias to throw off anyone who’d want to collect Brown’s bounty.

Stands up to redcoats and pays with his life

On March 5, 1770, just back from the Bahamas, Attucks was drinking at a Boston tavern with other seamen when a British soldier wandered in looking for work. (The troops were so ill-paid they needed other jobs.) The sailors taunted him and threw him out.

Later that afternoon, a mob infuriated by Britain’s new taxes pelted British sentries guarding the Customs House with rocks and snowballs. According to trial testimony, Attucks swung a stick at Captain Thomas Preston, fearlessly grabbed a soldier’s bayonet and urged the crowd to “kill the dogs, knock them over.” But the sentry wrested back his musket and shot him dead, the first of five colonials to perish that day.

Attucks and the other victims lay in state at Faneuil Hall for three days. More than 10,000 people took part in the march that conveyed their caskets to the graveyard.

Attucks is often considered the first patriot to die in the American Revolution, which began five years later. He became an inspiration for American rebels and later, abolitionists.

“Crispus Attucks, a Negro, was the first to shed his blood on State Street, Boston,” Booker T. Washington proclaimed, “that the white American might enjoy liberty forever, though his race remained in slavery.”

The University of Massachusetts History Club runs an online Crispus Attucks museum at http://www.crispusattucksmuseum.org. It includes photos of the commemorative silver dollar issued by the US Mint in 1998, the 275th anniversary of his birth.

Attucks’ path from obscurity to an immortal figure in American history began in Framingham in the humblest of circumstances 300 years ago.

RELATED CONTENT:

Black Heritage Trail highlights how Boston became an abolition hotbed (fiftyplusadvocate.com)

Storyteller and vocalist embodies her passion for history onstage (fiftyplusadvocate.com)