By David Wilkening, Contributing Writer

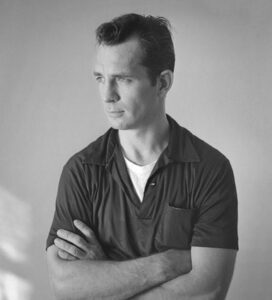

Photo/Tom Palumbo

LOWELL – Whether or not they have read his books, a must-stop for many visitors to this city is the final resting place of writer Jack Kerouac, one of America’s most famous travelers.

Grave site is magnet for admirers

The grave is near the gatehouse at the Edson Cemetery. At Lot 76, Range 96, Grave 1. So many visitors sought it out the caretaker printed a map with directions.

The simple slab on the grass has his name, birth and death dates. March 12, 1922. Oct. 21, 1969. His life started several years before America’s Great Depression. It ended when the U.S. President was Richard Nixon. The tribute on the gray stone is in capital letters: “HE HONORED LIFE.”

A larger commemorative stone added long after his funeral, located behind the grave, has a quote from his most famous book, On the Road. The quote is “The Road is Life.”

There are often hand-written notes and pens, or open bottles of Jack Daniels whiskey or half-empty wine bottles placed at the grave. They are appropriate since biographers agree the writer was an alcoholic. His lifelong affinity for cheap wine gave way to his older favorite: “boilermakers:” shots of whiskey and small beers that led to the alcoholism that caused his early death at the age of 47.

Kerouac’s books alone would have made him famous. A remarkable achievement since the French-Canadian spoke only in French until he was seven or eight years old. His book On the Road is regularly rated among the top ten American novels, top 50, or top 100―depending on which list you believe.

“TI JEAN” or “Little John” was Kerouac’s family nickname. Legend has it visitors to the grave include multiple jaunts by the Pulitzer Prize-winning folk singer Bob Dylan, known for his own famous words.

Kerouac had an influence well beyond literature

But it wasn’t just the admiration of songwriters like Dylan and that led to his fame. He was an influence not only in literature but also in film (Francis Ford Coppola), music (The Doors), politics (Barack Obama) and even fashion. The latter was illustrated as Dior Homme, under the creative direction of Kim Jones, which recently offered a collection that honored the Kerouac-created Beat generation in its Fall 2022 fashion show this past December. In 1993, The Gap famously featured Kerouac in an ad for its khaki pants.

Kerouac grew up in Lowell and was buried there. Oddly enough, he was hardly lauded in his native city during his lifetime largely because of his bohemian lifestyle, general rebellious nature, bisexual activities, and liberal use of drugs and alcohol. But today, it might be easily argued that he is Lowell’s most famous figure of the 20th century.

And visitors are expected to trek here from all over the world this year during the 100th anniversary of his birth in this faded industrial city of roughly 116,000 people, located less than 35 miles from Boston.

The year-long celebration has been going on throughout 2022. October will feature a weekend of Kerouac-themed events and tours, including a walking tour of historic sites often portrayed in his books.

For years, Kerouac was frequently on the move: New York, California, Lowell, and Florida. He spent time in Mexico and Morocco and had a brief sojourn in Paris. His wandering also led him to seek faith not only in his lifestyle, but in religion. He started out as an altar boy and a Roman Catholic, became an atheist, then a Buddhist, then a Buddhist-Christian. And finally, a straight Christian.

Writer felt he was often misunderstood

Even at an early age and years before his fame, Kerouac was a jazz lover who lived according to his own beat. During his time attending Columbia University in New York City, where he met other “Beat” figures like Allen Ginsberg, he often felt like an outsider. As “Lil’ Abner in big New York City,” as he put it.

Photo/Submitted

His reconciliation of the Buddhist tenet of reincarnation with Christianity’s afterlife of heaven and hell is what attracted retired Universalist minister Steve Edington to him years ago.

Edington is the president and a 30-year member of the Lowell Celebrates Kerouac committee. He leads tours of sites described in the books. He also leads tours in nearby Nashua, New Hampshire, where Edington was a minister. It was also home to both Kerouac’s parents, Leo and Gabrielle who met and married in Nashua before moving to Lowell.

Critics were often condescending

Kerouac often referred to his writing style as “spontaneous prose.” Although it was written purportedly without edits, he primarily wrote autobiographical novels based upon actual events from his life and the people with whom he interacted. His insistence upon “First thought, best thought” and his refusal to revise was controversial.

He typed “On the Road” on one continuous 120-foot roll of tracing paper in just three weeks, though he did some text revisions before it was published six years later. Kerouac also by all accounts resented critics such as novelist Truman Capote, who famously said his work was “not writing but typing.”

“That was a cruel remark and fairly typical of the reception he got from the literary community. I believe Kerouac knew of it,” said Edington, who is also the author of the book Kerouac’s Nashua Connection about his parents’ time there before they moved to Lowell.

Kerouac has often been called “Father of the Beats” or “King the Beats.” Jean-Louis Lebris de Kerouac (his real name) certainly paved the way for the hippie movement in the 1960s. But he didn’t like the designation. And it was only one way where Kerouac viewed himself as often misunderstood. When a television reporter asked him about coining the word “beatnik,” he denied it. He said instead, “I am a Catholic.” He coined the term “beatnik” in 1948 but viewed that as also misunderstood. It was not a reference to guitar and bongo-playing hippies but had a religious connotation, meaning “blessed.”

Other sites of interest

Photo/submitted

Edington says the author’s grave and his home at 9 Lupine Street in Lowell are the two mainstays most visitors want to see. The home is a private residence and there are no tours. But another common area of interest is the neighborhood on Beaulieu and Boisvert streets, which was described in the novel Visions of Gerard. That was a reference to Kerouac’s older brother, Gerard, who died of rheumatic fever at the age of nine when Jack was four years old. The writer idealized his brother and later said Gerard followed him in life like a guardian angel.

Still another area of interest: The Archambault Funeral Home. It’s where the wake was held for Kerouac. And the former St. Jean Baptiste Church, where he was an altar boy, and now a possible site of a planned Kerouac Center that is in its early fundraising stage.

Final years of anonymity

The writer spent the last six years of his life in St. Petersburg, Florida, where acquaintances said he often prized his anonymity. Few of his drinking buddies knew he was a writer. He hung out at a dive bar called “The Flamingo.” It’s the place that Kerouac is said to have had his final drink before being rushed to the hospital the next day for internal bleeding. For years afterward, the bar, now known as the “Flamingo Sports Bar” offered Jack’s drink for $2.50. It was called the “Jack Kerouac Special.”

Why was Kerouac an alcoholic? “It did run in his family,” Edington said. “My research showed his father and grandfather died early not from alcohol but it was a contributing factor. Maybe it was a genetic factor. But creative people often seem to have that (alcoholism) urge running through them.”

On his tours, visitors range in age from twenty-somethings to retirees Edington’s age and older. Why did the Beat writer attract such a diverse group? Edington, during his ministering in Nashua, gave sermons on the various religious aspects of the writer, despite his sometime amoral conduct. “He spent his whole life trying to figure out who he was,” he explained. “The idea of breaking away and struggling with ‘who I am and what am I doing here’ has an identity with different generations.”

And maybe with all his travel and his various religious conversions, Kerouac struggled but never found his own identity. Maybe he never found his God. But he shared with all of us his search for it.

For more information, visit https://lowellcelebrateskerouac.org.

New Bedford tells a whale of a tale (fiftyplusadvocate.com)

Essex and Ipswich remain havens for antiques lovers (fiftyplusadvocate.com)

Rockport’s ‘Paper House’ has endured for a century (fiftyplusadvocate.com)