By Dakota Antelman, Contributing Writer

SPRINGFIELD – There’s a wing of the basketball world focused not on NBA perfection, but on pickup game proficiency.

Historian Jeff Monseau sees that and thinks the sports’ Massachusetts-based founder, James Naismith, would be proud.

“He didn’t create basketball for these beautiful physical specimens who play the game today,” Monseau said in a recent interview. “He actually created it for the 50-year-old archivist who has a belly.”

Monseau describes himself as that archivist with a belly. He works for Springfield College in Springfield, Mass and says he’s not particularly physically active. Yet, he thinks about basketball on an almost daily basis.

Basketball’s “Paul Bunyan” style creator

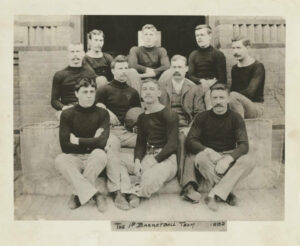

Springfield is the birthplace of basketball. Monseau’s college, in turn, evolved directly from the institution that employed Naismith as a physical education teacher while he crafted his game.

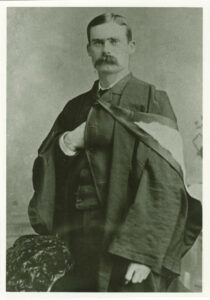

Naismith came to town in the late 1800s appearing, according to Monseau, as a “Paul Bunyan-like character.”

He had dropped out of high school to work as a lumberjack. He returned to school, though, and later earned a theology degree from McGill University. Through it all, he loved a variety of sports.

Religion’s opposition to early contact sports

While religious leaders at the time decried such an uncommon personal marriage of sports and faith, Naismith pushed forward supported, in part, by a few mentors in his college’s athletic department and by his own personal dogma.

“My life’s work is to do good to men, and [to] serve God,” Naismith wrote on his actual application to work as college physical director. “Wherever I can do that best, there I want to go.”

Monseau calls that physical document one of his “treasures” as an archivist. It describes, he feels, the essence of how Naismith thought about sports and his work.

“As he watched the game of basketball develop, the skill level went up, and the beauty of the sport went up,” Monseau explained of Naismith’s observations after inventing basketball.

“But, for him, the main thing would still fall back to the fact that he wanted more people to play the game.”

Modern growth aligned with basketball’s original intentions

Roughly 130 years after Naismith created basketball in a Western Massachusetts gym, that idea of growth and health drives modern efforts to bring people onto courts and keep them healthy into old age.

“You walk on a court and you’ve never met anybody,” Steve Bzsomowski of Never Too Late® Basketball said in a recent interview. “But some way or another, you all wind up working really well together…it’s the greatest feeling in the world.”

Never Too Late® is a Boston-based organization that runs basketball camps and clinics across the country.

Professional coaches lead drills and scrimmages to help players get comfortable enough in competitive settings to enjoy pickup or rec league opportunities in their communities.

With many players lacing up their sneakers into their 60s and beyond, Bzsmowski adds that safety remains paramount as coaches also teach players to adapt their skills according to physical limitations that come with age.

“We’re emphasizing playing in control,” Bzsmowski said. “…You don’t want to go there and have somebody whacking you. You don’t want to go for a layup and have somebody tackle you.”

A game built for everyday people

James Naismith was small, tough and focused on health. He liked sports but got beat up playing football. He then created a new game focused on reducing violence, promoting socialization and more.

Jeff Monseau, meanwhile, is a scholar. He studies Naismith and plays his game happily in informal pickup settings.

Talking about a sport he feels was built with accessibility in mind, he thinks back to Naismith in terms not unlike those used by modern basketball movers like Bzsmowski who simply want to expand the sport and keep people playing as they age.

“He thought it was a really good way to connect with other people to then hopefully make them better people,” Monseau said. “…If you could connect on a level that, you know, they would communicate at, then also you could affect how they would be.”