By Jane Keller Gordon, Contributing Writer

Photo/Jane Keller Gordon

Hudson – Some people think that remains of whole towns were left on the floor of the Quabbin Reservoir. Phyllis Hamilton Frechette, 94, knows for sure that everything was wiped out. She was there.

From 1930 to 1939, four towns in the Swift River Valley – Dana, Enfield, Greenwich and Prescott – were leveled and then flooded to create a water supply for Greater Boston.

Frechette remembers that buildings and the railroad – the “Rabbit Road” – were disassembled; cemeteries and monuments were moved; and trees and brush were cut down by men from Boston who were called “woodpeckers” for their lack of skill. Her life, along with the lives of 2,700 others, was changed forever.

In 2011, Frechettte published a small book, “Remembering Millington: A Village Swallowed Up by the Quabbin Reservoir.” It’s more about her recollections of the town than the Quabbin project.

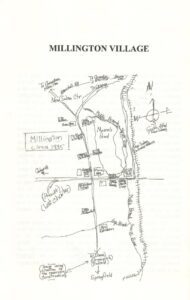

The book contains a hand-drawn map and details about the occupants of every house and every business in Millington. Frechette, along with her parents and four siblings, lived in a house that had been built by her grandfather.

“The whole main street was all family,” she recalled. “I clearly remember the house that we lived in.”

She describes the wood stove in the kitchen, lack of hot running water, pages of a Sears catalog used in place of toilet paper, a barn near the house, and a big garden where they raised produce for themselves and to sell at a roadside stand.

The village included a brick one-room schoolhouse, a general store, gristmill, “Moore’s Hall,” and a pond.

Her father had a florist supply business. He collected ferns and other materials, which he shipped by train throughout New England and New York. He hired men to work in their home to assemble Christmas ornaments.

She said in her book, “I remember hearing the wooden spools of wire tap, tap, tapping on the wooden tables as he would wound greens with wire for wreaths or to string for roping.”

In contrast to her specific recall about her home and Millington, Frechette said, “I don’t remember my parents saying much about what why the towns were being disincorporated and flooded. It was all about what Boston wanted. One-by-one, everyone, including my best friend, left and everything shut down.”

Her family was the last to leave their village. Frechette was 14.

“After the hurricane of 1938, the powers that be would not open the roads. We couldn’t get out except for roads that my father hacked his way out. Our house was taken by eminent domain. We had to move, and Millington didn’t officially exist at that point,” explained Frechette.

At the time of the move, Frechette was a student at a nearby school in New Salem. At the end of a school day, she was taken to her grandmother’s house in New Salem, three miles from her home in Millington, which she never saw again.

“My father bought the Millington general store and moved it to New Salem where he turned it into our house. He and my brother went back to Millington to bring it to New Salem, piece by piece. That way we held on to part of our past,” she said.

Frechette went on to earn a teaching degree from Framingham State College (now University), and a master’s in education. She taught for 32 years in the Newton Public Schools and East Providence, R.I. She has three children, six grandchildren, and a great-grandchild.

In 1995, at the age of 75, she graduated from the Andover Newton Theological School in Newton, and was ordained in the United Church of Christ in Canton.

She now lives on Lake Boone in Hudson.

“It’s such a peaceful place on the water,” she said. “I’m going to stay here forever.”